How the Black Sleeping Car Porters Shaped Canada

By Mel Toth

Black History Month, which has been officially recognized in Canada since February 1995, is a time for us to acknowledge the history and accomplishments of Black Canadians.

People of African descent have been shaping the landscape of Canada’s culture and history since the 1600s, although their stories and contributions have often been left out of the history books. In honour of Black History Month, we would like to highlight the history of a group of Black Canadians who have been instrumental in shaping our nation into the diverse, multicultural place that it is today: the sleeping car porters.

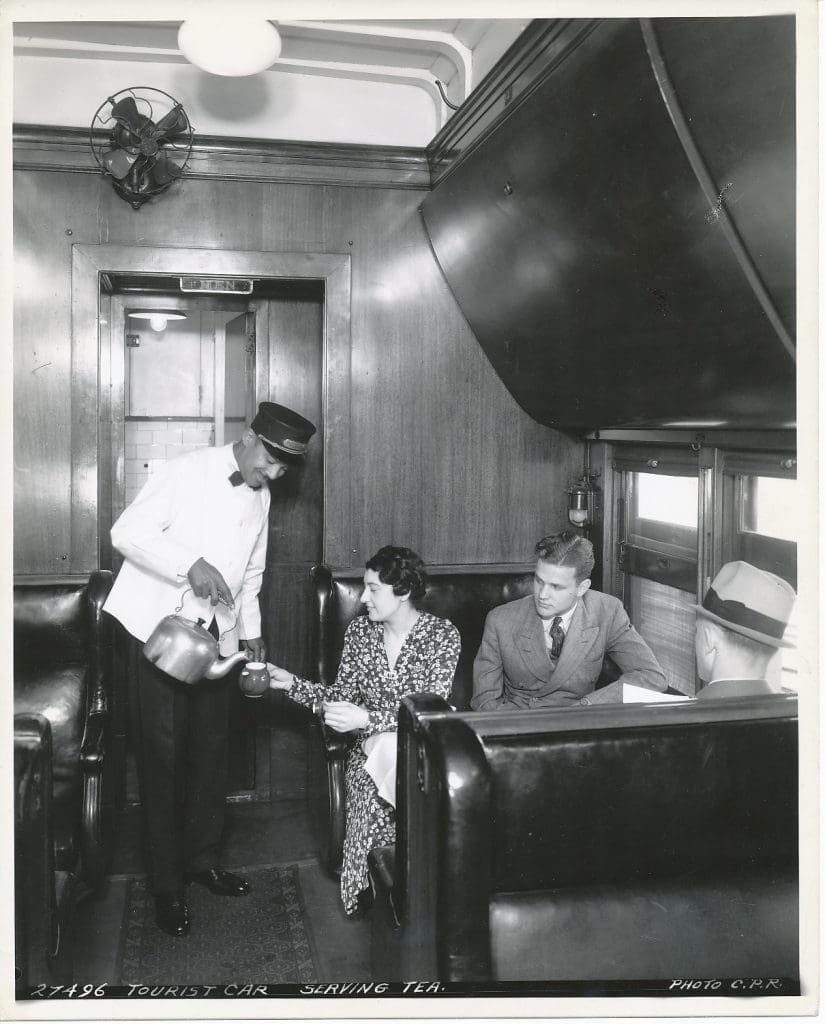

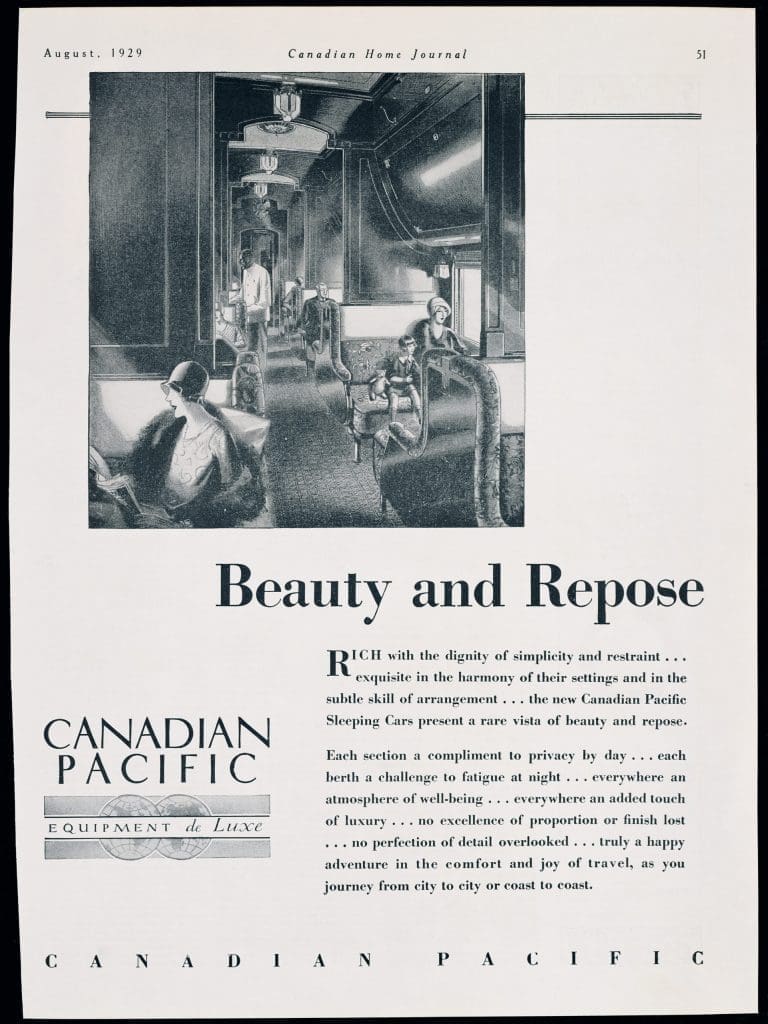

Historically, porters were exclusively Black men who were hired to work on the Pullman sleeper cars. Named after their American inventor George M. Pullman, these railcars were introduced to Canada in the 1870s and quickly gained popularity with railway companies. These train cars were the height of luxury, equipped with chandeliers and fine upholstery, privacy curtains and, of course, the famous Pullman sleeper bunks, which folded down from the wall to create sleeping berths for the passengers. As indicated by the name, the cars were designed for overnight travel, and their use by Canadian railway companies became increasingly popular over the next ten years.

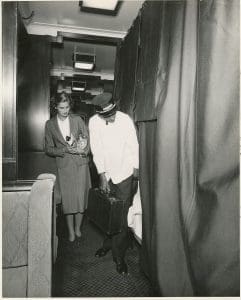

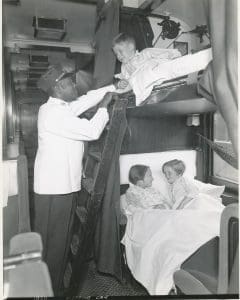

One of the highlights of traveling on the Pullman sleeper cars was the high quality of service provided. Each car was assigned a porter whose job it was to take care of the passengers’ every need: fetching drinks, making the beds, polishing shoes, carrying luggage, and so on. They also did housekeeping chores on the cars, such as cleaning the bathrooms and spittoons. The porter’s job was to make the trip as convenient and pleasant as possible for passengers. However, the porters themselves were not afforded the same courtesy: their job was demanding, exhausting, and demeaning. They were not allowed to sit with the passengers during their twenty-one-hour work shifts, but instead were given an uncomfortable folding chair to sit in while they were not serving. While on the train they were never truly off-duty – they were given three hours out of a twenty-four-hour day to sleep, but those few precious hours of sleep were often interrupted by passengers ringing porter bells for assistance. They had to sleep on a mattress on the floor of the smoking room, which was unpleasant and unhealthy because of the poor air quality.

Image: Black sleeping car porter assisting a passenger. CBK.1984.005.052

Image: Black sleeping car porter assisting young passengers. CBK.1984.005.054

A porter’s wages were low, and they had to use a portion of what little they made to pay for their meals, uniforms, shoe-shine kit and polish, and any items that went missing from their train car. They were also regarded as inferior to the white passengers they served – the position of porter, as it stood then, was inherently demeaning. The Pullman service model was based on slavery-era attitudes, and that service model migrated to Canada along with the Pullman sleeper cars. For example, Black porters were often called “George”, after George Pullman, a nod to the enslavement-era tradition of calling slaves after their masters.

If the working conditions were so poor, why, then, did these men accept the position? Many of them were highly educated, with university degrees in fields such as business, medicine, and science. They were overqualified, overworked, and underpaid.

Unfortunately, “as African Americans made significant gains into more highly skilled jobs, they were deemed by a mainstream workforce as a serious threat to white workers” (Grizzle, S.G., 1989, pg. 13). Career opportunities became increasingly scarce for Black workers, particularly in the world of train travel. Black railway workers who had once held positions as brakemen and firefighters lost their jobs. Although many of these men were highly skilled and educated, systemic racial discrimination affected both the hiring process and job security, and the best position they could aspire to was that of porter.

In addition to being excluded from higher-up positions, Black porters watched from the sidelines as their white coworkers gained protections and rights with the backing of unions and brotherhoods, such as the Canadian Brotherhood of Railroad Employees (CBRE), which explicitly denied “non-white” workers membership. However, the Black train porters did more than just watch. They began to organize. In 1917, the first Black railway workers union in North America, the Order of Sleeping Car Porters (OSCP) was formed by Black Canadian porters John A. Robinson, B.F. Jones, J.W. Barber, and P. White.

The OSCP faced an uphill battle in trying to secure rights and protections for its members. It had to combat institutional racism in the Canadian National Railway (CNR), which perpetuated the mistreatment of its Black employees, seeing them as “a cheap and disposable pool of labour who did not deserve job protections” (Tomchuk, T., n.d.). Even so, the OSCP managed to secure two contracts with the CNR, gaining greater job security and higher wages for its members.

The next challenge for the OSCP was taking on the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), an even more daunting task. The CPR was resistant to the unionization of Black workers and even forced employees to sign clauses promising not to participate in union activity. Thirty-six sleeper car porters – some of whom had worked more than a decade for the CPR – would be fired in the early 1920s for participating in union-related activity.

For the next decade, the porters would lie low, communicating in secret to unionize. Finally, in 1939, the Black Canadian porters were granted membership with the Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) in the United States, and with the support this partnership provided they were able to begin organizing in Canada. In 1942 BSCP divisions were established in Toronto, Winnipeg, Montreal, Edmonton, Calgary, and Vancouver. It wasn’t until three years later, however, that a collective bargaining agreement was reached with the CPR in May 1945. That same month, the CPR hired its first white porter, breaking half a century of segregation in the porters ranks.

Once the collective agreement was settled, the porters could finally push for changes to be made. They could demand (and received) fair wages, reasonable hours, a week of paid vacation, overtime pay, and fairer, more transparent disciplinary measures. They were allowed to put up plaques bearing their names in the cars they served. A berth was reserved for each porter on the car they served so that they could sleep more comfortably, and a better schedule for work and sleep was arranged.

Of course, the attitudes of racism persisted in the workplace, and the fight for equal opportunity and fair treatment was not over. There were still barriers to be broken down and injustices to contend. But now that the porters had the backing of a union, they no longer had to fear the unchecked power of the railway companies to punish and discriminate against them. They continued to build a better future for themselves on the foundation they had created, and in 1954, George V. Garraway, a former porter, became the first Black Canadian train conductor, breaking down yet another massive barrier which had prevented Black workers from being hired for higher positions.

The train porters fought an important and often-overlooked battle against institutional and systemic racism in Canada. They ultimately changed the shape and direction of our country as they fought for the equality and fair treatment of Black Canadians. In doing so, they opened the doors to others and “turned Canada black, brown, and a host of other shades” (Foster, C., 2019), paving the way for Canada to officially become the first multicultural country in 1971. We are a richly diverse nation today because of the efforts of the Black train porters to create a country in which all people can have equality and opportunity.

Sources:

Foster, C. (2019). They call me George: The untold story of black train porters and the birth of modern Canada. Toronto: CELA.

Grizzle, S. G., & Cooper, J. (1998). My names not George: The story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters: Personal reminiscences of Stanley G. Grizzle. Toronto: Umbrella Press.

Oyeniran, C. “Sleeping Car Porters in Canada”. The Canadian Encyclopedia, 19 February 2019, Historica Canada. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/sleeping-car-porters-in-canada. Accessed 26 January 2021.

Tomchuk, T. (n.d.). Black sleeping car porters. Retrieved from https://humanrights.ca/story/sleeping-car-porters

Heritage, C. (2020, February 21). Government of Canada. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/campaigns/black-history-month/about.html