How Canadians Learned to Shred: Skiing in Western Canada to the Mid 20th Century

By Emily Russell

Happy New Year everyone! This month, we are taking a look at the origins of skiing and how it evolved in western Canada into the mid 20th century. Skiing is a sport that many of us are familiar with, especially here in Western Canada. Rugged terrain, a copious amount of snow, and cold temperatures helped the sport grow simultaneously with our young country. This post is quite long so if you are not interested in the origins of skiing, skip to the “East vs. West” heading.

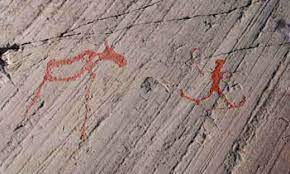

The Ancient Origins of Skiing

Depictions of skiing have appeared in cave drawings dating back to the last Ice Age. These prehistoric skis are a distant prototype to the ultralight, thought-out designs that we are accustomed to today. The images suggest that our ancestors strapped pieces of wood or branches to their feet to help get around in their frosty environment. Cave paintings and rock art depicting people on skis have been found in Norway, China, and Russia. One cave painting in China dates back to approximately 10,000 years ago, making them 2,000 years older than the earliest ski artifacts that we have on record.

Indigenous Methods

Indigenous peoples have lived in North America for thousands of years, experiencing harsher winters than we have faced in the modern era. The terrain and weather are somewhat similar to Northern China, Norway, and Russia, but Indigenous peoples of North America did not use skis. Instead, Indigenous groups across the continent used snowshoes and sleds to travel in snowy conditions. Snowshoe designs varied across the continent and were unique to different nations. Some designs have been named using shapes found in nature, such as the Bear Paw, Beaver Tail, and Swallow Tail. A pair of Bear Paw snowshoes were found in Ktunaxa territory which would suggest that this was a style used in this region. It is important to remember that Indigenous peoples are experts on the Canadian landscape. This land has never been empty, and the places that we love to explore have traditional names and stories.

Candad’s Medieval Conncetion

Skiing was most likely brought to Canada by Viking colonists when they arrived in Newfoundland in 1000 CE. Norsemen had two variations of skis. The first type was moderately wide and fairly long with a furrowed underside to help with up-tracking. The other style was twice as wide and shorter with fur fastened to the bottom. The wider skis were used more like snowshoes than downhill or cross-country skis. Many ancient skis used fur on the bottom to help with gliding down and grip on upward slopes, like modern climbing skins. There is no evidence to suggest that skiing caught on with Indigenous peoples living in the area during or after Viking settlement. Skiing disappeared for a few hundred years until the arrival of European colonizers.

East vs. West

Skiing in eastern and western Canada developed simultaneously, but population and cultural differences resulted in a few dissimilarities in the historical record. In the west, skiing was used as a tool first and for enjoyment second. Out east, skiing started to take hold as a fun way to exercise outdoors. Ski hills popped up around major eastern cities, especially in Quebec. Quebec was a hub for skiing, so much so that CPR introduced the “Ski Train” to take people from the city to ski hills. Easter Canada had the first ski instructor in the country, Emile Cochand arrived in Quebec in 1911. Cochand built the first Canadian ski resort just a few years later in 1917. In 1920, Alex Foster would turn the Canadian ski industry on its head. In Shawbridge during the 1920s, Foster used a 4-cylinder Dodge truck to create the first tow rope. Half a day cost 25 cents to hitch a ride to the top of the hill. His invention made skiing more accessible and gave skiers the energy to focus on form and technique. Downhill skiing would quickly catch on and replace cross country and ski jumping.

Photo of skier waving at the Canadian Pacific Railway Ski Train. CBK.2004.305.003

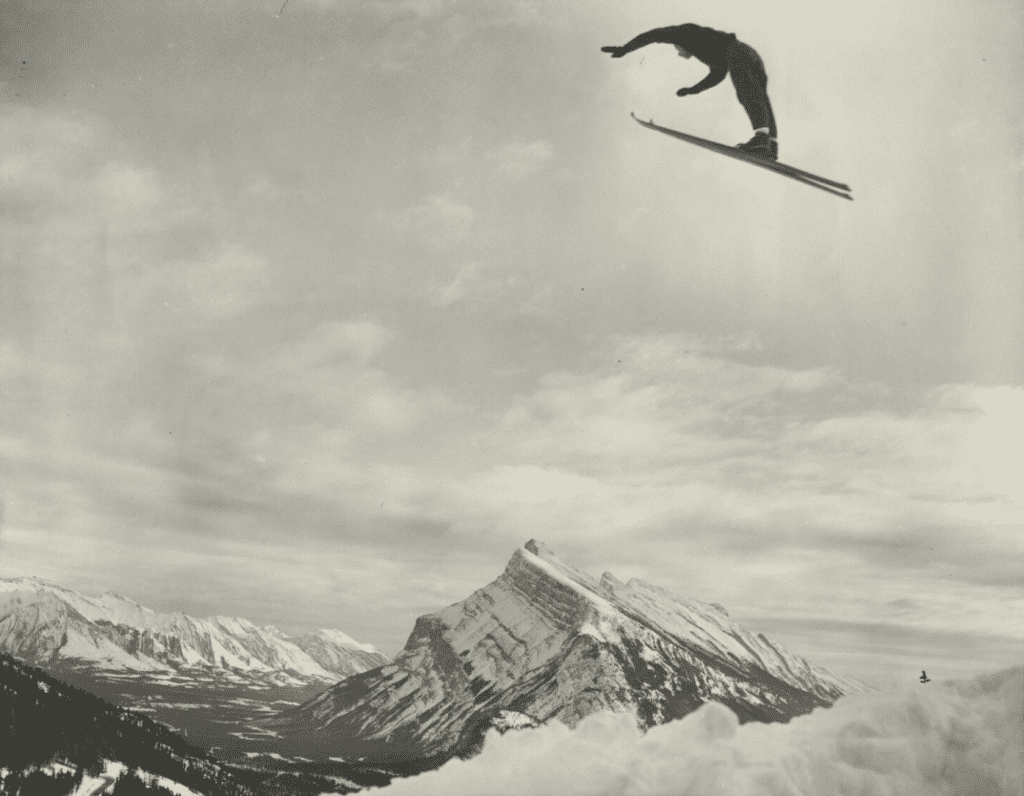

Out west, the development of national parks helped popularize skiing and attract tourists to the mountains. Banff is the best-known example of early professionalization in skiing. Guides were hired by CP to make mountaineering safer and more accessible for tourists. Ski clubs becoming increasingly popular throughout the west helped signify that locals were becoming more interested in the sport. Ski clubs created a need for ski jumps and brought in crowds of spectators. Ski jumping was the most popular ski event in the west into the 1900s. A shift towards downhill and slalom skiing came in the 1930s, but ski jumping would remain a spectator favourite in the modern era. This shift coincided with increased ski training for members of the Canadian military fighting in World War II, which may have contributed to the increase in popularity.

Connections to Industry

Like most things in Canada, industry played a large role in forming the industry. Mining and construction of the transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway line were two of the biggest attractions bringing European settlers to the mountains of western Canada.

Many mining towns in the mountains have since become ski towns. Kimberley, Fernie, Golden, and Revelstoke are some of the most familiar examples of mining towns turned tourist destinations. During the gold rush, Scandinavian prospectors used long wooden snowshoes, or gliding shoes, to travel through the mountains. The shoes were up to 4 meters in length and were also used in downhill racing. Revelstoke was introduced to “Norwegian Snowshoes” by a local miner around 1892. Large Scandinavian populations were the catalyst for ski clubs popping up in mining communities. Young people were drawn to the exciting and unusual sport. As mining towns grew, the populations started to diversify. Women and children were joining men, resulting in population growth and a desire for entertainment. It was a natural progression for skiing to become a popular choice amongst locals.

We cannot discuss the impact of the industry in Canada without addressing the impact of the railway. Construction of the transcontinental railway was a challenging process, and the mountain passes presented one of the greatest challenges of all, avalanches. Avalanches were not only a risk to human life but also took out infrastructure, slowed down shipments, and made for difficult clean-ups – especially in the 1800s. CP knew that the area near current-day Rogers Pass was especially dangerous and to help chart the safest path for the railroad, they hired Scandinavian mountain guides. These guides helped determine the safest route and where avalanche sheds were needed to keep the tracks as safe as possible. European mountain guides were called upon a century later during the construction of the Trans-Canada Highway.

Backcountry Skiing & Huts: Then and Now

Backcountry skiing and hut trips have become more mainstream in recent years. Many skiers are opting to avoid busy ski hills and venture into the mountains. Skiers going into the backcountry is reminiscent of the sport’s ancient origins with some modern upgrades and safety training. While in the backcountry, skiers will sometimes go on multiday excursions and stay in huts overnight. Skiers crashing in huts also has historic roots.

Sunshine Village was established by CP in the late 1920s as a summer lodge. In the winter, the lodge was more or less abandoned until skiers got their mitts on it – pun intended. These pioneers set the track for the area to become a world-renowned destination.

Mount Norquay has had a reputation for its terrain since the arrival of Scandinavian CP workers and Swiss mountaineers in the late 19th century. After a few decades, the mountain secured its place in history as being the site for one of the first cabins built with the sole purpose of housing skiers. A short while later, Mount Norquay would become the first official ski hill in the west. In 1929, Gus Johnson built a ski jump to teaching young children how to ski. A rope tow was added in 1949, establishing the mountain as a major attraction for adventure seekers.

In 1918 the government made a plan to construct a series of warden’s cabins in the mountains to shelter rangers patrolling the area. This plan took decades to complete. Construction of the structures did not finish until well into the 1940s. One such cabin is now the Egypt Lake Warden Cabin. This utilitarian cabin was built in the summer of 1942 and is historically protected. The cabin is now a hut for backcountry skiers to enjoy.

This is not where the story ends for the Canadian skiing industry. Skiing continues to be a substantial part of our culture and economy. The origins speak to how we got to where we are today. To learn more about avalanche safety, visit https://www.avalanche.ca/training.

Sources:

China’s Stone Age Skiers and History’s Harsh Lessons – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

Where did skiing come from? – BBC Travel

Discover the History Behind Sunshine Village | Sunshine Village (skibanff.com)

The History of Skiing on Mount Revelstoke – Mount Revelstoke National Park (pc.gc.ca)

THE ULTIMATE TIMELINE OF SKI HISTORY IN BANFF NATIONAL PARK — Crowfoot Media

Alpine Skiing | The Canadian Encyclopedia

Battling Avalanches | Land of Thundering Snow – Revelstoke Museum & Archives

Go Farther — Get Avalanche Trained

Facts You May Not Know About Lake Louise | BanffandBeyond

Then and now: The Lake Louise Ski Resort | SnowSeekers

https://www.pc.gc.ca/apps/dfhd/page_fhbro_eng.aspx?id=8315