Asian Heritage Month

by Mel Toth

May is Asian Heritage Month in Canada, an opportunity to look back and recognize the role of people of Asian descent in shaping the history of Canada. Their contributions to this country have built its history and helped to make it the richly diverse nation it is today, despite the fact that they have often been excluded from the narrative of Canadian history. Many Chinese immigrants came to the Cranbrook area during the 1858 gold rush and later during the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway. They settled in Cranbrook in what became the city’s Chinatown.

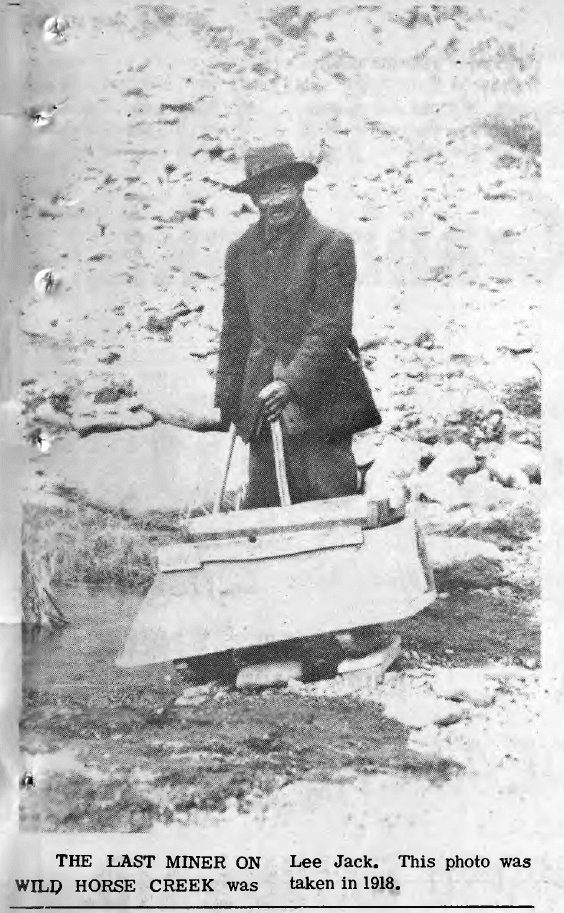

The first wave of Chinese immigrants came to Canada in 1858, when gold was discovered in the Fraser River Valley of British Columbia. These men, some arriving from San Francisco, others directly from China, were among the rush of international prospectors hoping to find their fortune in BC. One of these prospectors came to be a part of Cranbrook’s history, a man named Lee Jack. He came to Galbraith’s Ferry, now known as Fort Steele, in the 1860’s, one of the many searching for gold there. He was a placer miner, meaning he searched for gold in the deposits of the river using tools such as a rocker box, a device that would help separate gold from the dirt and gravel. Although many other Chinese prospectors would move on to find work in other sectors, starting businesses in towns or working for others, he remained there for decades, even after others had left. He often lived off small wild game while he continued to search for gold, sometimes turning up small pockets of it but never enough to make his fortune. He died in hospital in May of 1929 and was remembered by the Cranbrook Courier as being cheerful and uncomplaining, no matter his circumstances.

From 1881-1884, the Canadian Pacific Railway needed workers to complete the construction of the railway. Many of these labourers were Chinese immigrants from California and China – by 1882, approximately 6,500 out of 9,000 workers on the railway construction were Chinese. This was the start of the second wave of Chinese immigration to Canada. Although these workers were essential to the completion of the railway, they were treated much differently than their white coworkers. Chinese workers were paid $1.00 a day compared to the $1.50-2.50 that white workers were paid, and while white workers were provided with food and gear, Chinese workers had to pay for their own out of their already-low wage. They were also given the most dangerous tasks such as using explosives to break up solid rock. Due to workplace risks and harsh conditions, hundreds of Chinese workers died building the railway. When the railway was finally completed and memorialized in the famous photograph of CPR Director Donald Alexander Smith driving in the last spike, Chinese-Canadian workers were cleared from the scene and excluded from the photograph, despite the contributions they had made to completing the railway and the terrible losses they had suffered in the process.

After the completion of the railway, many Chinese workers were put in a difficult situation: although their labour had been so essential to the construction of the CPR, they were not valued as “desirable citizens” of Canada. Provincial laws and policies were put in place to restrict the rights of Chinese residents, and in 1885, the Chinese Immigration Act was put in place, levying a head tax on all Chinese immigrants. This entry fee would continue to increase over the years as the government tried to restrict the number of Chinese immigrants entering the country, until at last, in 1923, the new Chinese Immigration Act was passed. This new law, under the same name as the old one, drastically reduced the number of Chinese immigrants coming into the country, and was the only law restricting a group of people from entry into Canada based solely on their race. Only students, diplomats, Canadian-born Chinese returning from education in China, and certain merchants were allowed to enter the country. Every person of Chinese descent, whether Canadian-born or not, had to register for an identity card, and the penalties for noncompliance were strict. Even those who were allowed to stay in the country were treated as second-class citizens and were often excluded from the rights and privileges of white Canadians, including the right to vote or to own property.

Because of the head taxes, and later the new Chinese Immigration Act, up to 80% of Chinese men had wives and children still living in China. They were unable to sponsor their family members to join them in Canada, and it was often too expensive for them to visit frequently. Because of this, associations that provided community for these “married bachelors” were important to the Chinese community. One of these such institutions was the Chinese Masonic Lodge in Cranbrook, where groups could meet and participate in their community.

In a personal memoir, Hank Lee writes about his mother, Hoy Ngui Yee Shee, who came to Canada with her husband, Lee Chow Nam, and settled down in Cranbrook. She would often provide vegetables from her garden to those in the community who did not have enough of their own, and shared traditional herbal remedies with those who could not afford or did not trust Western medicine. Hoy Shee was one of the few in Cranbrook’s Chinatown who had a family of her own to take care of, and although things were difficult financially, she still helped provide for those who were on their own.

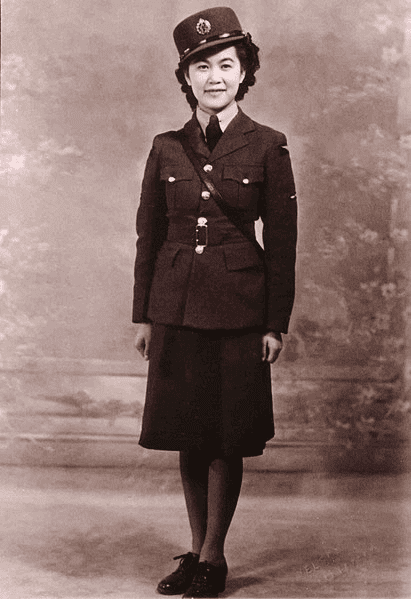

Despite the limitations that were put upon their rights and the hardships they had to endure to create their lives here, Chinese-Canadians continued to contribute to Canada. Jean Lee, the eldest daughter of Hoy Shee and Lee Chow Nam, grew up in Cranbrook. When the Canadian military began accepting volunteers of Chinese descent in 1942, Jean Lee enlisted. She became the only Chinese-Canadian woman accepted into the Women’s Division of the RCAF. After completing her basic training in Toronto, she would continue to serve until the war ended in September 1945. During this time, she was invited to meet Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King in 1943. She was also placed on the honour guard of China’s first lady, Madame Chiang Kai-Shek, during her visit to Canada in June of 1943. Her brothers Wilson and William Lee also served in the Canadian military, Wilson with the RCAF in 1945 and William in the Korean War.

It is important to take the time to remember the contributions of Asian-Canadians to the culture and history of Canada. Although they have not always been included in the narrative of our nation’s history and had to fight for their place in it, they have been an essential part of the fabric of Canada, including our own town of Cranbrook, BC.

Read more:

Jean Suey Zee Lee of the RCAF – Cranbrook Daily Townsman (cranbrooktownsman.com)

Chinese Immigration Act | The Canadian Encyclopedia

Events in Asian Canadian history – Canada.ca

Building the Railway – Province of British Columbia (gov.bc.ca)

Gold Mountain – Province of British Columbia (gov.bc.ca)